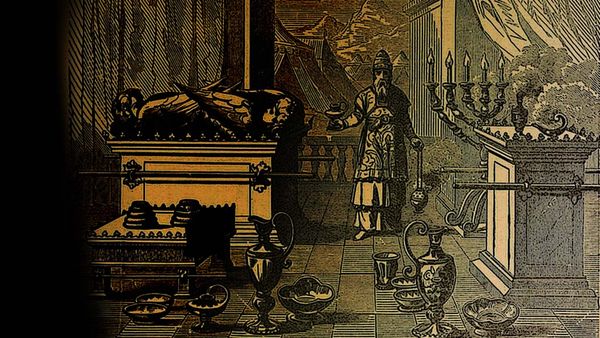

A handful of ancient Israelite inscriptions feature an enigmatic title that has been variously translated as “governor of the city” and “commander of the fortress.” Who was this figure? This late eighth-century B.C.E. bulla discovered near Jerusalem’s Temple Mount displays the inscription le-śar ‘ir. BAR author William M. Schniedewind contends that the translation “the governor of the city” is incorrect and that the inscription should refer to the ancient Israelite military title “commander of the fortress.”

In 2017, archaeologists announced the discovery of a late eighth-century B.C.E. seal impression (bulla) during the wet-sifting of dirt excavated from the Western Wall plaza next to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. The bulla features two figures holding what may be a sun disk—a Judahite royal symbol—and an inscription that reads le-śar ‘ir. The archaeologists translated the inscription as “the governor of the city,” and the rare seal was celebrated in the media. Schniedewind contends, however, that the seal should instead be translated as “commander of fortress,” and in his BAR article, he explains why the distinction is important—both to understanding the development of the Hebrew language and script and to understanding Judahite bureaucracy.

Schniedewind points to a number of other eighth-century inscriptions that include the phrase le-śar ‘ir. For example, inside the fortress of Kuntillet ‘Ajrud in the barren land of northeastern Sinai, three storage jars dated to c. 800 B.C.E. were discovered with the inscription le-śar ‘ir. The fortress of Kuntillet ‘Ajrud served as a military outpost and waystation. Schniedewind discusses the translation of this inscription in BAR:

The spelling of this title in Hebrew without the definite article—thus “commander of fortress” instead of “commander of the fortress”—reflects an early stage of the Hebrew language before the use of the definite article (“the”) had been standardized. Although this title is usually translated as “belonging to the governor of the city,” this translation does not at all fit at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, which was no city. In this instance, the title can refer only to the person in charge of a small fortress during its heyday around 800 B.C.E. The (mis)translation reflects the development of the Hebrew word ‘ir, which later came to mean “city.” However, these inscriptions prove that the original meaning of ‘ir could be applied to a much smaller walled settlement, like a small remote fortress.

As the point where three of the world’s major religions converge, Israel’s history is one of the richest and most complex in the world. Sift through the archaeology and history of this ancient land in the free eBook Israel: An Archaeological Journey, and get a view of these significant Biblical sites through an archaeologist’s lens. Going back to the inscription found near the Temple Mount, Schniedewind explains why he believes in translating le-śar ‘ir as “the governor of the city” is incorrect:

The word śar is a loanword from Akkadian, and it refers to a military commander or an officer. We find the term in a number of Hebrew inscriptions, including Lachish Letter 3, line 14, which refers to “the commander of the army” (śar ha-ṣaba’). A complaint from an agricultural worker at the small fortress of Metzad Hashavyahu is also addressed to the śar. It seems likely, then, that the title in the seal impression from Jerusalem should be translated as “commander of (the) fortress.”

Indeed, it makes little sense to think of it as a civilian title since the king also resided in Jerusalem. Rather, the parallels for this title indicate that this was the military commander in charge of the fortified town of Jerusalem—or perhaps, more narrowly, a fortress within Jerusalem.

Source: Biblical Archaeology, 2019

Member discussion