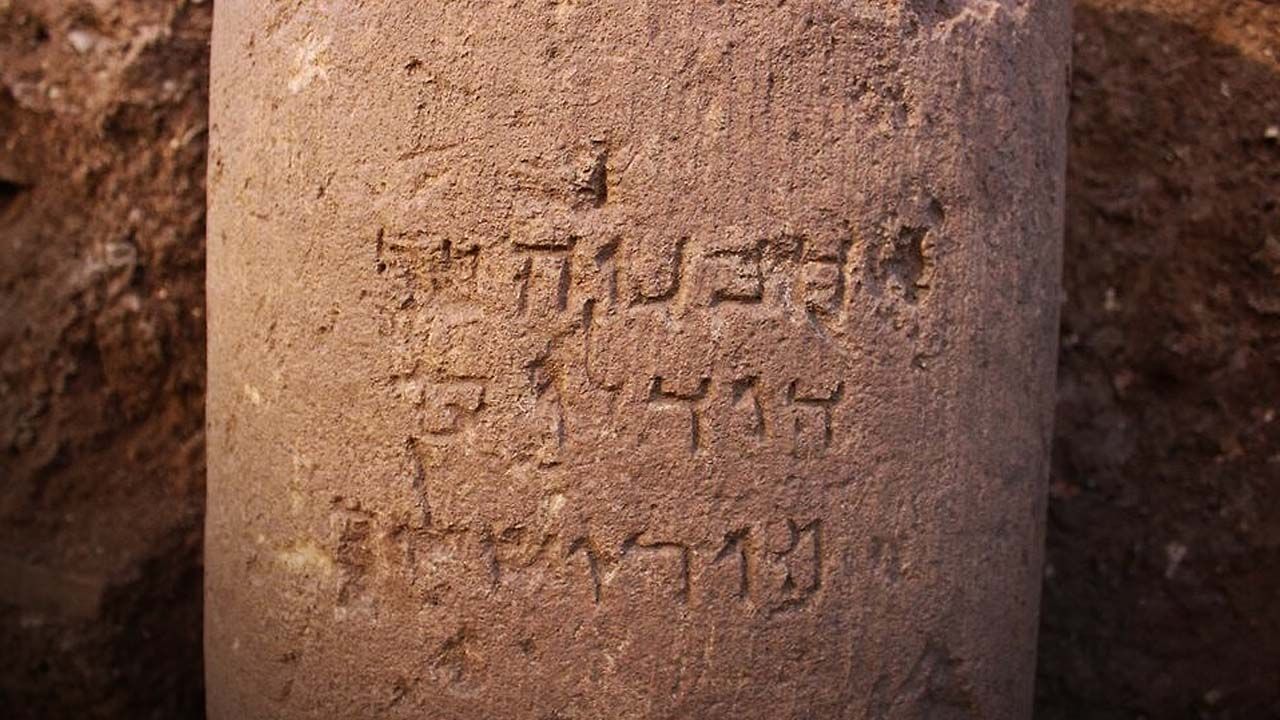

During the winter of 2017, archaeologists working in a Jerusalem suburb, discovered the foundations of a Roman structure dating to the 1st century B.C.E. What they found was building remnants and a part of a common round column. The exiting part is that the column had writing on it. Etched on the column was the oldest known inscription of the city’s name spelled out in full in Hebrew script. When people talk or write about Jerusalem today they call the city Yerushalayim in Hebrew. But in ancient times, a shorthand spelling was often used -Yerushalem. In fact, of the 660 times that Jerusalem is mentioned in the Bible, only five instances use the full spelling. The column inscription reads “Hananiah son of Dodalos of Jerusalem.”

The limestone drum on which the inscription was found recently went on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The stone appears to have been repurposed from a building even older than the Roman structure in which it was used. According to a statement from the museum, the inscription was written in Jewish Aramaic, a Semitic language commonly spoken by Jews of the ancient world, which was written using Hebrew letters. According to experts, the style was typical of the era when Herod the Great, who ruled over Judea from 37 to 4 B.C., during the Second Temple Period.

“First and Second Temple period inscriptions mentioning Jerusalem are quite rare,” Yuval Baruch, an archaeologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority, and Ronny Reich, a professor of archaeology at Haifa University, note together in the statement. But it is the unique spelling of Jerusalem that really makes the stone special. The full version of the city’s name has been found on just one other artifact from the Second Temple Period: a coin dating between 66 and 70 A.D., a period of Jewish revolt against the Romans.

Archaeologists don’t know who Hananiah son of Dodalos was, though they have a theory about his occupation. The name “Hananiah” was common in ancient Israel, but “Dodalos” is an unusual name. It might be a modification of “Daedalus,” the craftsman from Greek mythology. Perhaps Hananiah and his father, then, were craftsmen? According to Danit Levy, one of the archaeologists who has been leading excavations in the area, the stone inscription was found near the largest ancient pottery production site in the region of Jerusalem.

The ruins themselves indicate a pottery operation—kilns, water cisterns, pools for preparing clay, workspaces for drying and storing vessels. The area known as the potter’s quarter was active for three centuries. During Herod’s reign, the production seems to have been focused on cooking vessels, and activity at the site continued on a smaller scale following the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. Of course, archaeologists can’t say for sure where the column drum originally came from. It may have been brought to the potter’s quarter.

Original Sources: Haaretz and Smithsonian

Member discussion